In memory of Peter Killingbeck Bowers (1950-2018)

Its almost a month since my wife's uncle, Pete, passed away after being diagnosed with cancer earlier this year. He was 68 years old.

One of his last requests was to be cremated in Inverness, where my wife's parents live. Prior to his death, there was a tentative plan to bring him north so he could spend his final days in a hospice near to most of his close family. Sadly, he ran out of time.

Being an avowed atheist, and disavower of most cultural norms, Pete had asked for a humanist funeral. Two weeks ago, a handful of family and friends gathered at the small chapel at Inverness Crematorium, taking our seats to the husky intonations of the late Leonard Cohen. Pete was present, as the thread binding us together in our mourning. I'm travelling light.

The minister was keen to treat proceedings as a celebration of Pete's life. As my father-in-law gave the eulogy, waves of emotion breaking up his words, I wondered if the minister had misjudged the mood of the mourners. There was palpable grief among those who knew Pete well, more than the minister was prepared for and perhaps more than Pete himself might expected. I imagine he would have been touched by this, though he may also have wondered what all the fuss was about.

Impossible to speculate about the thoughts of the dead. In reality I didn't know Pete all that well, and am probably the least qualified person to speak of him with any authority, much less eulogise him. I can only write about the Pete I know, who is a different Pete to the Pete my wife knew, who is a different Pete to the Pete her parents knew, or the Pete known to his parents, and so on.

This, however, poses another problem: what right have the living to write about the recently deceased at all? How can we possibly condense the complexities and contradictions of an individual's character into a few paragraphs of prose? Particularly when we measure the value of another's life against the credo by which we live our own; especially when words and actions can be misinterpreted and misconstrued. And if selfhood is multiple, all biographical studies will only ever be partial?

In Pete's case, retracing the steps of his life is made all the more difficult by a paucity of information about some of his movements. There are known knowns, and known unknowns. Some of the information is sketchy. The lost take their stories with them, and we are left to fill in the blanks.

After working for his father's photography business upon leaving school, he left to pursue other interests. He spent time as a photographic printer and delivery driver in London, lived on a canal boat in Amsterdam and even spent in Libya working for the Gadaffi regime. He enjoyed music and was a skilled self-taught guitarist. Later in life he was in a loving relationship for a number of years, until his partner's untimely death from cancer. Pete nursed her through her illness, something that affected him deeply and perhaps contributed to his dogmatic approach to his own diagnosis.

Pete's life was unconventional, and it certainly was not without colour. There are some things we can definitively say that Pete did: he did whatever he felt like, by and large. Pete once told me that he had taken every drug under the sun, and while its true he was part of that generation that tuned in, turned on and dropped out in the late 60s and early 70s, he did not strike me as a drug casualty. He was too astute for that. Too hard-wired to reality to want to escape it.

There was something faintly prodigal about Pete, standing slightly at one remove from the rest of the family. During his eulogy my father in law recounted that Pete's childhood bedroom was in an annex separate from the main house. That seems fitting. He liked, I suspect, to be a man apart. Those who are comfortable with solitude recognise that trait in another.

We met several times, either at the home of my wife's parents usually over the Christmas period, or on the rare occasions that he visited our home in London. We got on well. I enjoyed his company, his acerbic sense of humour and occasionally protracted diatribes against some injustice or other. He always poured himself an extra glass of wine after dinner, never did the washing up and smoked in a non-smoking household. He livened things up a bit. I liked that.

When we first met, he was in the middle of a protracted battle with a large housing association. His west London flat, and the block it occupied, were due for demolition. The other tenants had already moved on but Pete was absolutely determined not to quit his flat until the association found him acceptable alternative accommodation. For months and months he refused to yield, and this dogged display must have caused untold irritation and aggravation within the offices of the association.

Pete enjoyed kicking against the pricks. At this time I was working for the lobbying organisation that represented landlords. Back then I was trying quite hard to become a photographer, taking photographs almost constantly. We didn't talk about work but Pete seemed to instinctively know I hated my job, and was desperate for a way out. Given his associations with photography, I was quietly pleased when Pete showed some interest, without being overly critical or sycophantic about the photographs I had taken. He showed me the plate camera his father had owned, and we talked about taking some photographs with it another time.

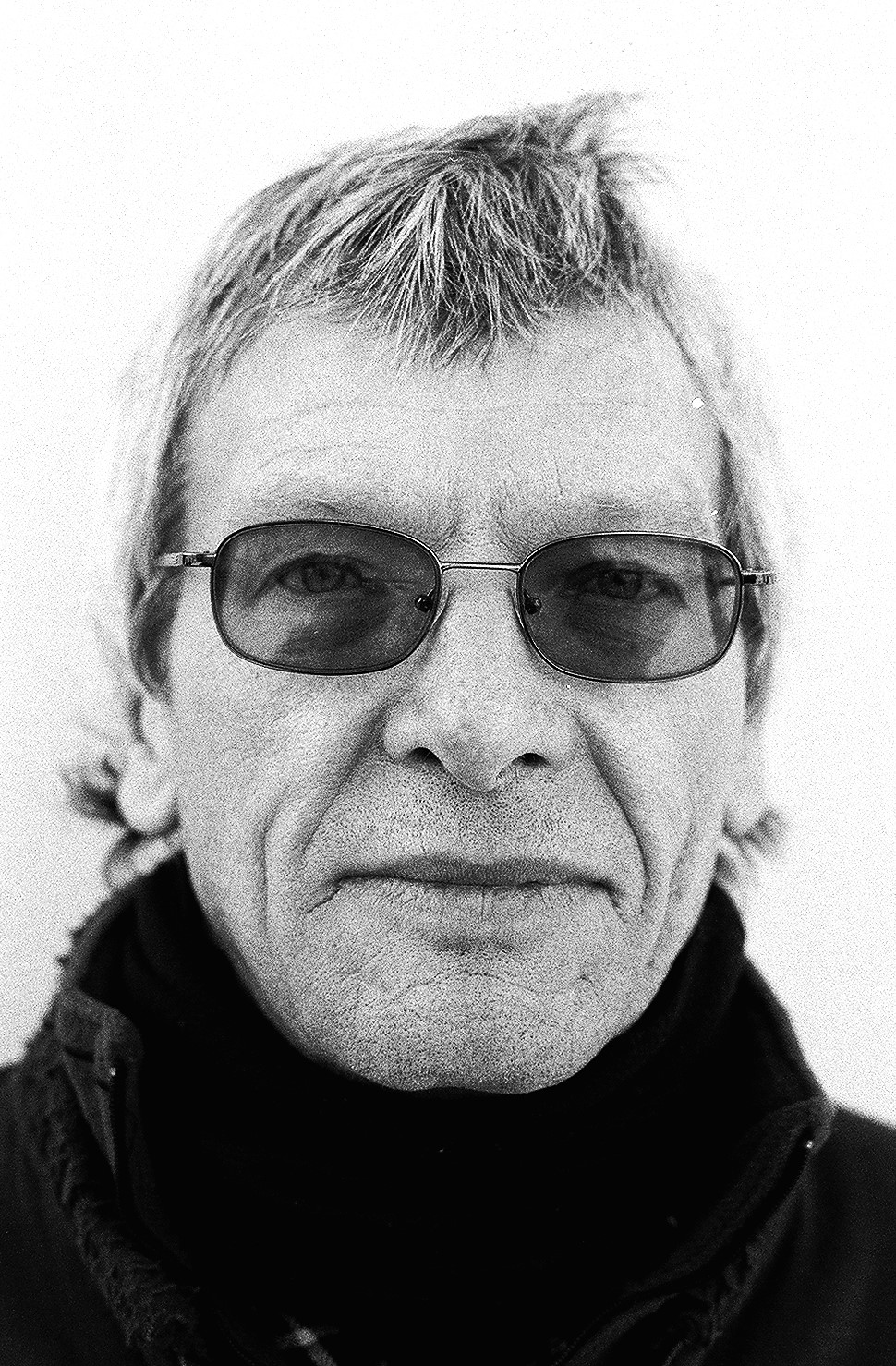

One particular Christmas it had snowed heavily in the Highlands, and we were holed up at the in-laws remote cottage. Also cognisant of my burgeoning interest in photography my mother in law had very kindly set up a little darkroom in one of the upstairs bathrooms, with a very antiquated That day I took some portraits of the family and after dinner Pete and I spent a couple of boozy hours in the dark making prints of the negatives I'd developed that day. Pete was able to make perfect prints just from looking at the images under the lens of the enlarger. He seemed particularly chuffed with the print of his sister, but my favourite portrait is his: there is an intensity about his gaze which captures him precisely at that moment.

On another visit we were walking through Inverness, me trying to take photographs, him trying to engage me in conversation, when we passed a charity shop. In the window display we spotted two old Olympus SLRs, virtually antique and in perfect condition. While I ummed and ahhed about buying one, or both, Pete launched into a negotiation over the price, during which he managed to convince the two ladies behind the counter to knock off a tenner. I began to see how he'd managed to survive for all those years under the radar.

A couple of years later Pete came for lunch at our old house in Sydenham. He had brought over a ten rolls of AGFA Vista film which he'd stashed in his loft from way back when, saving me the best part of fifty quid. Several were used in tandem with the Olympus SLR for my Land of Eagles series.

After lunch I had to run out on some errand or other and Pete came with me. As we made our way along Adamsrill Road and past Mayow Park we passed the time chatting about something I can't recall now. I left him at the bus stop on Sydenham High Street, shook his hand and walked on. That was the last time I saw him.

After our family relocated to Scotland I hoped to see him again; that he would have come up, stayed for a few days, stretched out his legs and got comfortable, as he always did, listened to some records and shared some whiskey. Helen's parents were half-expecting Pete would move into their place in Inverness in the coming years. There would have been time to do all those things. Retrospectively, there always is. Regrettably, it wasn't to be.

Rest in peace, Pete. We'll miss you.